Mosaic art experienced a revival in the second half of the 19th century, following Gian Domenico Facchina’s invention of the indirect method of laying mosaics, developed for the mosaics of the Opéra Garnier. This technique significantly reduced production costs and encouraged a decorative use of mosaics, a trend that continued through the Art Nouveau and Art Deco periods.

It was only after the Second World War that artists began to embrace mosaic work—some directly, others by collaborating with specialist mosaic workshops to bring their projects to life. Fernand Léger was one of these artists. He sought to restore the monumentality of certain works through the medium of mosaic.

We are in Plateau d’Assy, which, between 1930 and 1960, was a renowned centre for sanatoriums in Haute-Savoie. Here stands the church of Notre-Dame de Toute Grâce, whose façade is entirely covered with a monumental mosaic by Fernand Léger.

The church became the arena for an ambitious Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art, devoted to the renewal of sacred art. The project was entrusted to Canon Couturier, himself a painter and sculptor, who believed that only contemporary art had the power to infuse the sacred where religious art had failed: “To keep Christian art alive, each generation must call upon the masters of living art.”

This vision led to the exclusive commissioning of contemporary artists—believers and non-believers alike—to adorn the church. The result brought together a great diversity of mediums—mosaic, painting, sculpture, stained glass, ceramics—supported by architecture designed in the spirit of a “total art”.

Mosaic and Architecture Intertwined

Covering the façade of the church, a 172 m² mosaic draws us inside.

The project began with a meeting in 1945 in New York between Fernand Léger and Canon Couturier. In 1946, Couturier entrusted Léger with the decoration of the church façade. For a long time, Léger had wanted to integrate monumental works into architecture. Returning to France after his exile in the United States from 1940 to 1945, he embraced the opportunity.

“The Assy church project was a major event in my life as an artist. I had long awaited the chance to create a mural in an architectural material. This became possible in mosaic thanks to the decision of Abbé Devemy and Father Couturier. I was able to compose this ensemble in bright colours without destroying the architecture… it is, I believe, the first time that this collaboration between architecture, painting, and sculpture has truly found its place.”

Fernand Léger

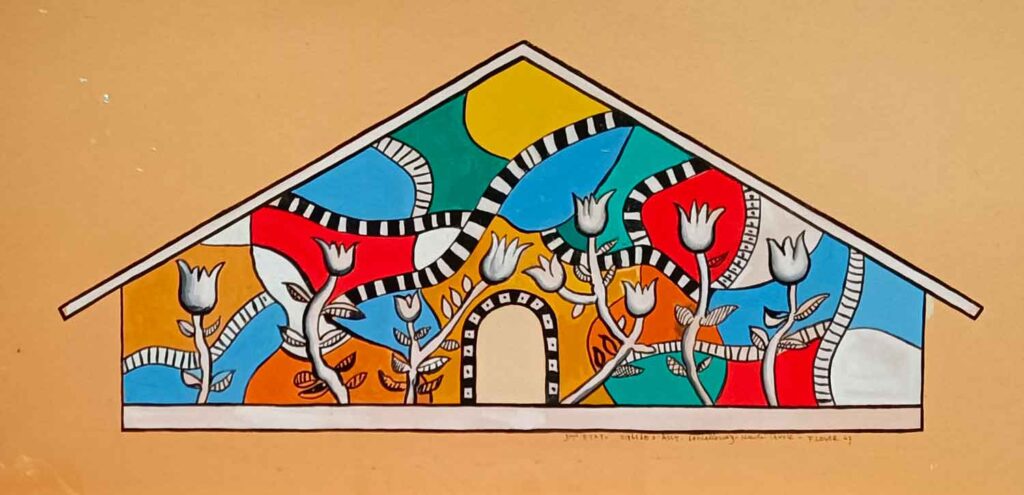

In 1947, he produced several designs on the theme Litanies of the Virgin. Large areas of vivid colour brightened the massive sandstone building.

Mosaicists at Work

Léger collaborated with mosaicists Paul Bony and Pierre Gaudin of the Gaudin workshop in Paris, which remained active until 2006 and was celebrated for its expertise in monumental works, mosaics, and stained glass. Many artists, including Jean Bazaine, Marc Chagall, Alain Manessier, and Georges Rouault, worked with this atelier.

The creation process followed a clear division of labour:

- The preparatory cartoon was designed by Fernand Léger.

- Paul Bony, who was also a stained-glass artist (and created the church’s stained glass), interpreted and adapted Léger’s cartoon for mosaic.

- The Gaudin workshop produced the mosaic itself.

The Italian indirect method—first used for the mosaics of the Opéra Garnier—was employed. The work was prepared in the studio, then installed on site. Materials included mainly glass tesserae and enamelled ceramics, offering a rich chromatic range to reproduce the vivid colours of Léger’s design.

Archival records from the Léger Foundation indicate that the artist took an interest in the project without directly participating in the execution, though he regularly met with Pierre Gaudin and was involved in material selection. The mosaic was completed in 1950.

A First Experience that Led to Many Others

Although Italian painter and mosaicist Gino Severini criticised Léger’s work at Assy, the project only reinforced Léger’s desire to explore mosaic further. Severini remarked:

“Léger created a kind of deck of cards, where he drew, in the same style as the ace of hearts or diamonds, the attributes of the Virgin Mary… Her head is one of Léger’s usual heads, surrounded by rays. And that’s it.”

Severini suggested that Léger, being new to mosaic, may not have anticipated the discrepancies between the drawn cartoon and the finished work, unlike in his large murals for the 1935 Brussels International Exhibition or the 1937 Palais de la Découverte, where he had retained direct control.

Nonetheless, the Assy project greatly contributed to the revival of sacred art and, more broadly, to the collaboration between architects and artists. Following this first monumental mosaic, Léger received commissions worldwide to integrate his work into architecture and public spaces:

- The auditorium of São Paulo

- The university campus of Caracas

- The United Nations Headquarters

- The foyer of the Maison de la Radio in Paris (ceramic mural)

- The Hamburg velodrome stadium

- The Paul Éluard school in Villejuif (ceramic murals)

He also designed models and projects for UNESCO’s Mur pour la Paix (Wall for Peace), which remained unfinished at his death in 1955.

A Brief History of the Church’s Origins

In 1937, Father Jean Devemy, chaplain of the Sancellemoz sanatorium where he was being treated for tuberculosis, initiated the construction of a parish church. Architect Maurice Novarina was commissioned, and the building was completed in 1942.

Devemy, along with Canon Marie-Alain Couturier—painter and sculptor, and driving force behind the artistic project—was determined to restore the sacred to its rightful place in religious art by engaging with modern art. Couturier believed that sacredness could be expressed through contemporary artistic creation.

From 1938 to 1956, an exceptional artistic programme took shape under the motto: “Art must be returned to the Church, and the Church to art.”

Renowned artists were invited to contribute, regardless of their faith: Jean Bazaine (stained glass), Pierre Bonnard (painting), Georges Braque (painting), Marc Chagall (ceramics, stained glass, bas-relief), Jean Lurçat (tapestry), Fernand Léger (mosaic), Germaine Richier (sculpture), Georges Rouault (stained glass), Théodore Strawinsky (mosaic), and Matisse (ceramics).

This approach provoked strong opposition from the Catholic hierarchy—Pope Pius XII condemned what he saw as “depraved works that must be banned or removed from the church.” The controversy over involving non-believing artists delayed the church’s consecration until 1950, with Germaine Richier’s crucifix at the heart of the scandal.